What do the two Koreas mean to third-country born

children?

More than 50% of defector schoolchildren are now of

third-country origin

Damin

Jung September 28th, 2017

When

South Koreans hear “defectors,”

they usually think of Koreans that speak the same language, albeit with the

distinctive North Korean dialect. So when you visit a school for defector children

in the South, you might wonder why more than half now speak in Chinese.

“My name is Chun-mi, and in Chinese pronunciation, it’s Chun

Mei (春美),” says

one student at the Durihana International School, an alternative school for

defector children in Seoul.

Chun-mi

is the 17-year-old child of Su-jin Joo, who defected from North Korea 23 years

ago, and she was born in China.

Out

of the roughly 30,000 North Korean refugees residing in South Korea, 71 percent

are women. For most of them, the process of defecting takes a long time: anything

from six months to eight years if things are delayed.

Many

of them marry Chinese men after being sold by brokers. Chun-mi’s mother was

one of those who chose to cross the Tumen river. Though she was aware of human

trafficking in the border areas, she

believed life in China would be better than life in the North, where she languished

in poverty.

Growing

up in the Chinese province of Henan before coming to South Korea two years ago,

Chun-mi never knew her mother was from North Korea.

“Her accent was bit different, but I just thought it would be

that she came somewhere far in China,”

Chun-mi says. “I never knew there was a country called North Korea.”

“I came to South Korea in 2015 but it was in 2016 ? the time

I started to speak Korean ? when I first found out there is North Korea.”

Adjusting to life in South Korea can be even more

challenging than it is for those who directly came from the North

Pastor

Chun Ki-won of the Durihana Mission, who has been helping defector families

including Chun-mi and her mother, says that many third-country-born children

grow up not knowing that one or both of

their parents are defectors.

“They would not know unless their mothers tell them,” Chun

tells NK News. “However, most of the defector mothers hide where they are originally

from and how they were trafficked to forcibly get married, which is why their

children do not know they are defectors.”

▲ Chun-mi’s mother Soo-jin crossed Tumen River 23 years ago |

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The

number of third-country-born children in South Korea is increasing, with the

number of those currently enrolled in South Korean schools now outnumbering

young North Korean defectors, representing 1317 out of 2517 students enrolled

- 52.3% - at the end of December 2016, according to the MOU.

With

the increase in the number of North Korean refugee families with children born

in third countries, the South Korean government has extended the one-time grant

of KRW4 million (USD$3482.04 at the time of publication) for defectors to those

born outside the peninsula.

Though

the new policy is notable progress in the welfare provided to the growing number

of third-country born North Koreans in South Korea, it seems educational support

is more urgent, especially when it comes to language and culture.

“I never knew there was a country called North Korea”

For

children not born in the North or the South, adjusting to life in South Korea

can be even more challenging than it is for those who directly come from the

DPRK: they have to learn a completely different language and culture at the

same time.

“I do not feel that I am from the same country when I see South

Korean people,”

Chun-mi says. “In China, if I see people on the street, I just smile and talk

and it is so natural, but in South Korea, if I just look at people on the street,

they would think I am weird.”

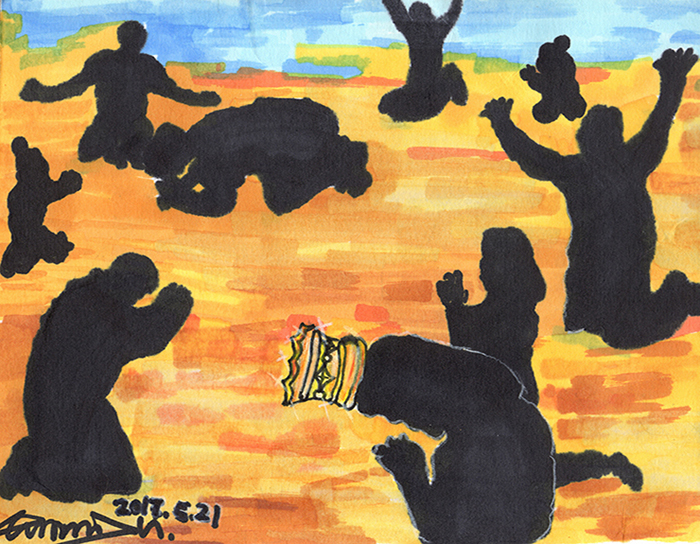

▲ In a dream, Chun-mi saw Jesus praying for her in the middle

of a desert

Since

many defector mothers have no choice but to spend most of their time working

for a living and away from their children, kids like Chun-mi often feel isolated

in a totally new country, Pastor Chun explains.

“The children get more stress after coming to South Korea,”

Pastor Chun says. “When they were in China they were able to talk and have friends

but after they came to South Korea in the hope that they now would live with

their moms who they were desperate to see, they find the reality is not like

that.”

Like

many of the children of defector families, Chun-mi has often been left home

alone waiting for her mother, who has run a restaurant since last year.

The

loneliness and pressure Chun-mi had been going through, she says, was not noticed

by teachers and friends, and not even by her mother, and led to her attempting

to take her own life by jumping from a balcony.

The

incident saw Chun-mi diagnosed as paraplegic, with a doctor saying it was not

likely that she would walk again.

Defying

expectations, however, she is walking again, and her life in South Korea had

dramatically changed. Receiving attention and care from her mother, friends,

and teachers made her feel loved and she has since become more outspoken.

“The children get more stress after coming to South

Korea”

The

media attention on her story saw her talent for painting be recognized by educators

and opened up new opportunities to study painting abroad, in Germany and the

U.S.

“I just draw paintings when I feel lonely and have nothing to

do, and when I draw, I just don’t think of anything but draw things,”

Chun-mi says.

▲ Chun-mi’s paintings were introduced at an exhibition in Berlin

| Photo: DAMSO Galerie & Teehaus

After

Chun-mi’s story was broadcast on TV, her paintings were also introduced in

an exhibition in Zehlendorf (Berlin) on September 10, by DAMSO Galerie &

Teehaus, a private gallery in Berlin.

Many

third-country-born children in South Korea, though they often do not know about

the division of the peninsula before coming to the South, see both Koreas as

home.

“After I came to South Korea, I once went to the border area

with my mom,” she says. “It was New Year’s Day and my mom was looking at

North, towards her hometown there. I could feel her nostalgia.”

“I just draw paintings when I feel lonely”

Chun-mi

was awarded the grand prize at 18th “Happy Peaceful Unification Writing and Painting Competition,”

for

her painting of the Mugunghwa (South Korea’s national flower), the Korean peninsula,

and tiger posing with victory hand gesture.

“My mother is also a North Korean and my friends also came from

the North,” Chun-mi says. “I really want to see unification since I know how

my mother and friends feel… I wish the two Koreas could be united.”

Edited

by: Oliver Hotham