Korea's

Underground Railroad

Effort

to free refugees from Communist North gets more dangerous, frustrating

Oct. 20, 2011

By Josephine Jung Taipei, Taiwan

Reverend Chun Ki-won has many mouths to feed.

His family is bigger than the average household: Mr. Chun

is responsible for taking care of the North Korean refugees living at his shelter

in South Korea, as well as rescuing as many as of the 200,000 North Korean refugees

hiding out in China today as he can.

Mr. Chun operates a modern Underground Railroad, which helps

defectors from Communist North Korea escape across the Chinese border and make

the long and dangerous trip to a life of freedom in South Korea. After defecting,

North Koreans must journey through China, hiding from Chinese officials to avoid

being sent back to North Korea. The ultimate goal is to reach Southeast Asian

nations where they are recognized as political refugees and wait to be sent

to South Korea. Mr. Chun works with Durihana, a mission group devoted to this

cause.

“It’s mentally grueling and terrifying for the defectors

making the trip,” says Mr. Chun. “If one person is caught, the rest of the

group, as sad as it is, must keep moving. Most defectors say that they would

sooner kill themselves rather than be sent back.”

North Koreans began crossing into China in greater numbers

beginning with the food crisis in 1997. The Kim Jong-Il regime takes resources

and allocates them to party loyalists, leaving the rest of the population to

starve, with no other choice than defecting as a means for survival. Defecting,

however, is a serious crime in North Korea, punishable by imprisonment, torture

and death. Families who have a member who has defected are subjected to equally

cruel punishments.

China does not accept North Koreans as refugees, despite pressure

from the U.S. and the international community.

“China expatriates North Koreans that are hiding in China

back to North Korea, in defiance of international human rights laws,” says

Mr. Chun. “Those who are caught and sent back are subjected to cruel public

executions. Attendance is mandatory, even for children who are not yet 10. It

is a message, to instill fear in the people and discourage them from defecting.”

Most of those who make it to South Korea safely are still

separated from family who stay behind. Mr. Chun works to contact and bring out

the families of the refugees he has rescued.

But now, it seems, the opportunity of escape is getting narrower.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult for North Korean refugees

to escape out of North Korea and China,” says Mr. Chun, with a dark expression.

“China doesn’t want these North Koreans flooding over the border, so they’ve

tightened border security. North Korea in turn, has also become more severe

with border security on their side, because of the power change in the Kim regime.

… There is a new policy in North Korea of immediately shooting anyone who is

trying to defect.”

Scott Snyder, a Senior Fellow for Korea Studies at the Council

on Foreign Relations, says the strengthening of border control is the main reason

it's getting harder to get out of North Korea.

The flow of defectors "has been stanched due both to

pre-Olympic security sweeps on the Chinese side of the border and measures on

the North Korean side to strengthen border security,” Mr. Snyder says.

Sokeel Park, a research and policy analyst at LiNK, a humanitarian

organization similar to Durihana, says that while it is becoming harder for

North Koreans to leave, “the Underground Railroad is fighting those trends,

and with time the people operating the Underground Railroad gain experience

and hopefully it gets better established. But there is a constant battle with

authorities.”

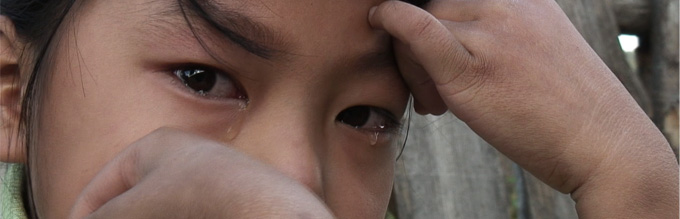

Angela (name altered to protect her identity) is one of the

North Korean refugee who was rescued by Mr. Chun in 2002. Her dream is to be

able to give children the education that she was denied by becoming a teacher,

she says. Angela is 25, an age at which most take advantage of their youth and

pursue their dreams. But Angela does not have that luxury-because she is North

Korean.

“I left school when I was 12,” she says. “It was a better

use of time to go find food than to go to school. The priority was to live.”

This is the case for many North Koreans, says Mr. Chun.

Angela comes from Musan, in the northern part of North Korea,

right next to the Duman River, which marks the border between China and North

Korea. She escaped North Korea at age 16 in search of food, and spent six years

wandering in China until she found out about Mr. Chun’s organization. She contacted

him immediately, and he arranged for her escape through missionary workers stationed

along the Underground Railroad.

North Korean defectors who cross the border are often sold

as commodities. Mr. Chun says although they suffer human rights violations such

as forced prostitution, refugees are powerless to do anything about it because

of the threat of being sent back to North Korea.

“I am one of the luckier ones, because I didn’t have to

sell my body or [be] trafficked,” Angela says. “There were others around me

who were subjected to much worse, but I couldn’t do anything but watch.”

With Angela now safe in Seoul, Mr. Chun now faces the task

of helping her sister, brother in-law and nephew out of North Korea. So far,

his efforts have been unsuccessful.

“We’ve had incidents where the guides who we pay to lead

the group of refugees out of China were frauds and cheated us,” he says. “Many

try to swindle rescue mission funds, by telling us that they will help the refugees

and then disappearing after they have been paid.”

Angela waits nervously.

“We’ve tried to bring them out once already," she says.

"They were caught and taken to a prison in North Korea, and the soldiers

beat my sister and her husband unconscious."

Mr. Chun says it's frustrating not to be able to do more.

"With Angela’s family, we have to tread carefully, because North Korea

will show no mercy to those who attempt to defect more than once.”

“It’s also difficult because I can’t be there myself,”

says Mr. Chun. Mr. Chun was arrested and imprisoned in China in 2002 when he

was on one of his rescue missions. Caught trying to smuggle people illegally

out of China, he has since been barred from entering China, and monitors each

mission remotely from South Korea.

That task is only getting more difficult, due to tighter border

policies on both the Chinese and North Korean sides.

“I want to give hope to these North Korean refugees. But

what they’ve gone through is unspeakably horrible, and it’s hard to make things

better for everyone,” says Mr. Chun. “A lot of the time, I’m frustrated and

disappointed because it’s unimaginable that such horrors exist today. My job

has a lot of sadness come with it.”

So why does he do it?

“Because I can’t sit here and just watch them suffer the

greatest pain known to mankind,” he says.